Scientific watchmakers have created a prototype of a nuclear clock, hinting at future possibilities for using atomic nuclei to make precise time measurements and make new tests of fundamental theories of physics.

While the definition of “watch” is scientifically nebulous, the prototype has yet to be used to measure time. So it should technically be called the “frequency standard,” says physicist Jun Ye. But the work brings scientists closer to a nuclear clock than ever before. “For the first time, all the essential ingredients for a working nuclear clock are contained in this work,” says Ye, of JILA in Boulder, Colo.

While atomic clocks measure time based on electrons bouncing between energy levels in atoms, nuclear clocks measure time based on the energy levels of atomic nuclei. A certain frequency of laser light is needed for an atom or an atomic nucleus to make such a jump. The electromagnetic wave motion of that light can be used to tell time.

Nuclear clocks would keep time using a variety of the element thorium, called thorium-229. Most atomic nuclei make energy jumps that are too large to be triggered by a tabletop laser. But thorium-229 has two energy levels that are close enough to each other that the transition between these two levels can serve as a clock.

Now, researchers have pinpointed the frequency of light needed to initiate that jump. It’s 2,020,407,384,335 kilohertz, Ye and colleagues report on Sept. 5. Nature.

Most importantly, measurement has an uncertainty of 2 kilohertz. This is more than a million times the accuracy of the previous best measurement. And it’s more than a billion times the accuracy with which this frequency was known just over a year ago, highlighting multiple successive developments.

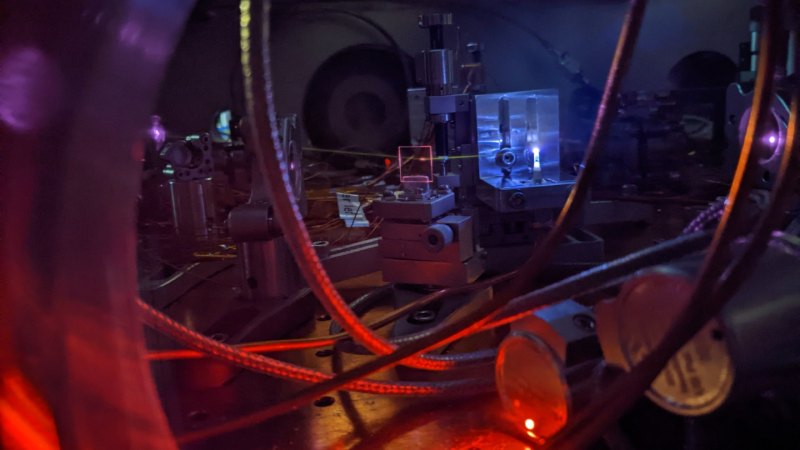

The enhancement depends on a component called a frequency comb (SN: 10/5/18). An essential component of many atomic clocks, a frequency comb creates a series of discrete frequencies of light. The use of a frequency comb with thorium-229 has been a major research goal, for some scientists (SN: 6/4/21). In the new work, Ye and colleagues compared the ticking of the nuclear clock with that of an atomic clock of a known frequency.

“This is something that will be important as a scientific application for tests of fundamental physics,” says physicist Ekkehard Peik of the National Institute of Metrology in Braunschweig, Germany, who was not involved in the new research.

In the future, such comparisons can be used to search for strange physical effects, such as shifting values of fundamental constants (SN: 11/2/16). These are numbers that – as the name implies – are believed to be eternally fixed.

#prototype #nuclear #clock #hints #extremely #accurate #timekeeping

Image Source : www.sciencenews.org